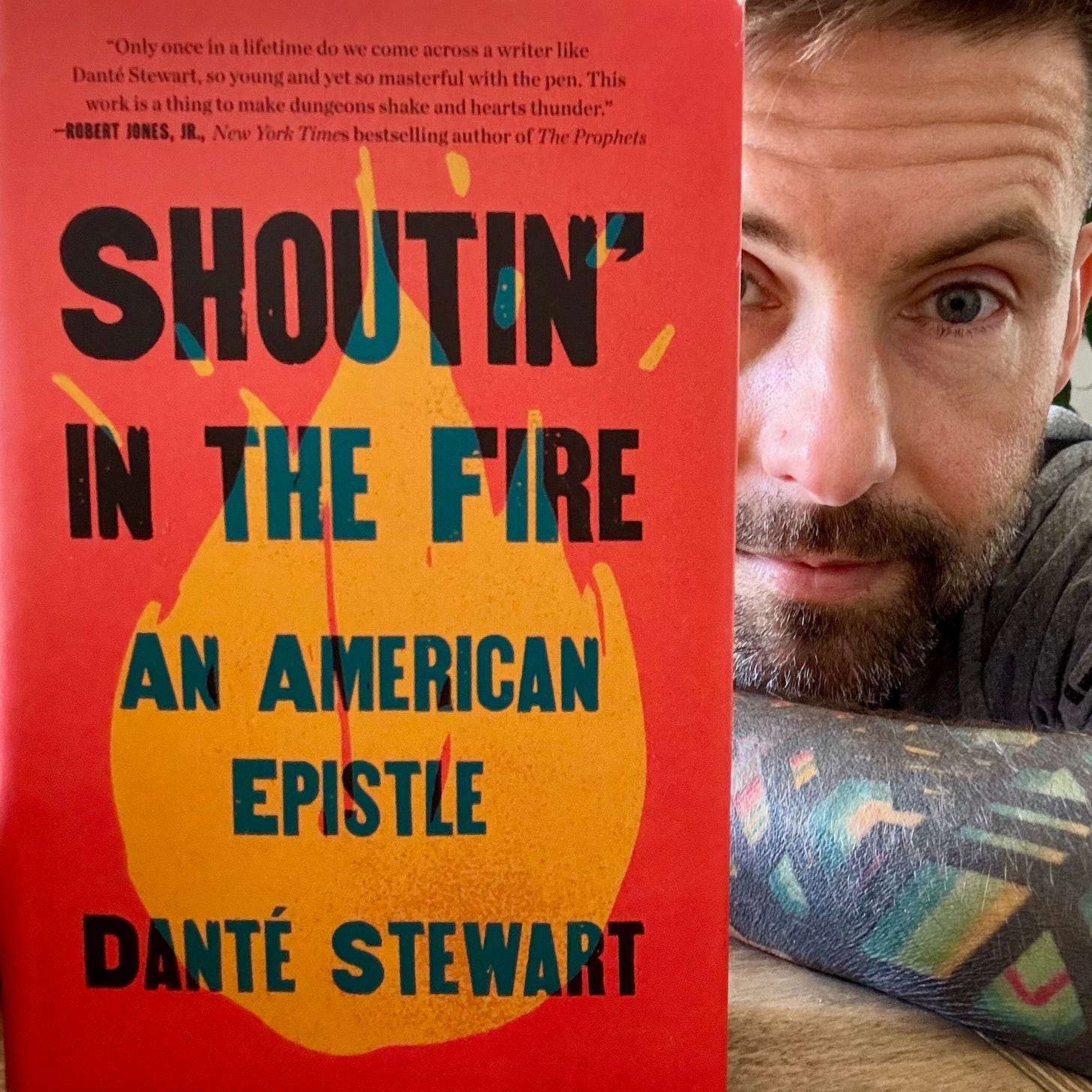

Growing up as the son of a Southern Church of Christ minister, and having been a minister myself, I am deeply stirred by the writings of Reverend Danté Stewart. His book Shoutin’ In The Fire: An American Epistle has done more to ignite me about racial justice than well-known conceptual works of our era because Stewart’s memoiristic prose brings me close…

Keep reading with a 7-day free trial

Subscribe to GETTING TO NAKED to keep reading this post and get 7 days of free access to the full post archives.